This piece was published by The Island Review in February 12, 2019.

Extraterritorial

In 1917, my great-grandfather Alfredo Baquerizo Moreno was the first president of Ecuador (in nearly a century of them) to set foot in the Galapagos. Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, the archipelago’s capital, honours his heed.

It is safe to say that, at the time of his visit, few among his connationals gave the islands much by way of thought, and those who did probably thought of them as little more than an acneic constellation on the face of the Pacific. As with so many black legends, their ill-repute was first established following their European ‘discovery’ by Tomás de Berlanga, the Bishop of Panama who became windlocked into almost dying of thirst there in 1535. Nor could the inductive cataclism wrought upon the worlds of faith and science by Darwin only decades earlier, and initiated by the five weeks that he spent there, have earned them favour in markedly Catholic country.

Considering that ‘out of sight is out of mind’ is the half-spoken dictum of Latin American governance, Baquerizo’s visit to these hinterlands may have struck some as untoward, impolitic, out of character. While I lay no claim as to what exactly drove my ancestor to San Cristóbal, in a man of such storied judgment the lure may have been deeper than just checking up on penal colonies and whaling ships. It may have been as deep, perhaps, as what had driven Melville out to sea as a young man, in a journey that would also take him to the Encantadas, earlier, in 1841. It may as well have had do with Baquerizo’s kind of polymathy which, though not entirely uncommon at the time, was certainly unusual in his place: as a trained pianist, poet, translator and novelist who was fluent in several languages and made a living as a legislator before being invited into the morass of South American politics, there must have been some pleasure in discovery involved.

As a man of many forms –πολύτροπος— one can also conceive that he was open to incentives of another order. The archipelago is bewitching as well as bewitched. In his first “Sketch” on The Enchanted Isles, Melville spells out that:

“…there are seasons when currents quite unaccountable prevail for a great distance round about the total group, and are so strong and irregular as to change a vessel's course against the helm, though sailing at the rate of four or five miles the hour. The difference in the reckonings of navigators produced by these causes, along with the light and variable winds, long nourished a persuasion that there existed two distinct clusters of isles in the parallel of the Encantadas, about a hundred leagues apart. Such was the idea of their earlier visitors, the Buccaneers; and as late as 1750 the charts of that part of the Pacific accorded with the strange delusion. And this apparent fleetingness and unreality of the locality of the isles was most probably one reason for the Spaniards calling them the Encantada, or Enchanted Group.

It is probably, if not provably, one reason for the Spaniards to have kept them at the safest possible remove. The Galapagos are a reverse Aeaea in which men are transformed into tortoises and the genius of the place is not a sorceress but a superior mirage.

Antiaeaea

One version claims my uncle Ronald Norris was, like Wyndham Lewis, born in international waters. By other counts, he first deplaned into the world by water, aboard a British ship facing the shoreline of Lobitos. Another, less credible, source, has him born in Lobitos itself, which would have rendered him a native islander regardless, since the township –delimited by signage in English that curtly forbade entrance to Peruvians and dogs— was developed for and by the functionaries of the region’s British oil interests.

What’s more certain is this: Norris was responsible for bringing Lloyd’s reinsurance to Ecuador and, when he first arrived in the Galapagos in 1988, it was to find that most boat owners there did not think to insure their crafts; or rather, that they uniformly felt themselves to be included in the cloaking clause of the angelus novus in charge of climatic (and anticlimactic) affairs. Over time, Norris was able to pick up the slack where the angel left it in gross dereliction of duty, and through all of this pulling and sorting he found himself as the head of two families, with one of them in San Cristóbal.

His six youngest children, who shared in this half-life with him, were soon granted the resident status that was felt to be unglamorous at the time, but that increased in value as soon as it became almost impossible to acquire. Though they have since found purchase in the cities –they, like their father, flicker back and forth between them and the islands— my cousins are clearly part atoll, part human.

Norris kept a delicate entente with the Enchantresses for many years. They would call to him and he would go to them –some pulls are not to be resisted, but negotiated— but he never committed to staying with them. Apotropaically, he lived in Quito, another intensely volcanic enclave, although far from the sea. It is a matter of concern, however, when a restless animal (un)settles into sleep having not thoroughly encircled its nest; or when a certain type of man decides to buy a house. He may have known his time was nigh as well, as he reported to his wife that this –the island, San Cristóbal— was where he had chosen to die.

A house is a dead-end, and the trip that Ronald Norris undertook to buy his was his last. He died at sea, somewhere between the Enchantresses and mainland Ecuador; perhaps in international waters. Only my cousins, his children –for all of them were children at the time— were on board with him that day. Six children –his children— sailed his lifeless body back to Guayaquil.

Saint George the Lonesome

He was found, alone, in isla Pinta, as if he had sprung fullyformed—nay, fullgrown—from the forehead of a chtonic demiurge. It is presumptive to assume he need have been one of a kind. Why not a one-off, just once?

Melville could have entertained the possibility, considering his first Sketch on The Encantadas summons the “long cherished superstition” of seafarers who thought that –and again, this returns us to Antiaeaea— wicked mariners were turned into giant tortoises (in a spirit not disparate from how the vanguard of Odysseus’ crew was turned into swine.) That it didn’t take their fellowmen –known for eating anything under duress— too long to figure out these tortoises were hardy enough to be kept as a living canned good with a full year’s lease on expiration in their travels only ratifies the cogency of Fate.

So let’s presume George had been a contender. Perchance he had been someone in the vein of the ambiguously-named William Ambrosia Cowley, a Prospero among pirates who had arrived in the archipelago aboard Cook’s Bachelor’s Delight. The year was 1648 and, in England, William Petty was inaugurating an important chapter in the history of human rights by starting to profit from his “Declaration Concerning the newly invented Art of Double Writing”.

Not all men are made to draw distinctions from very fine differences. Cowley was able to trace and name, not one, not two, but eight of the Gallipagos after illustrious colleagues and/or English royals. But to name is, naturally and unnaturally, to wield authority. Can one be blamed for thinking the Enchantresses may not have had much patience for Cowley’s A[ca]damic posturing?

Of course, being tortoised is not always punishment enough –some men are suited to the life of reptiles— and these long but finite (or)deals are often chock-full with redemptive options. As such, Cowley –now the tortoise George— was immersed in an oceanic solitude, but with it came the time and pacing from him to embrace the terms of his divine humiliation. What is a century to sanctity and its attainment? (And what are sanctity and attainment in the greater scheme of things?)

The two clutches of eggs that George was able to produce with genetically-adjacent females proved unviable. So passed a solitarian in the line of Jonathan of Saint Helena and St. Turpen of the Pitcairns.1

Depth Perception

Darwin may have been the first man, white or otherwise, to see the islands through their own eyes. This is not to say others had failed to note the facts that would inform his transformative insights: the remark on how “the tortoises differed from the different islands, and that he could with certainty tell from which island any one was brought” was, after all, afforded him by Nicholas Lawson, the Norwegian-born acting governor of the Galapagos at the time of his visit. Nor was it that Darwin was uniquely able to connect the (moving) dots between the different-shellgames-on-different-islands and his mockingbird samplings, since his theory of evolution was famously coeval with Wallace’s.

The difference may be Darwin disembarked in Chatham with his mind tuned to the timescale of geology. What first drew his eye was the archipelago’s Brahmanic breathing of —we know it now— more than 20 million years; a sequence of magmatic and explosive setpieces that predated the appearance of life on Earth and will continue irresistibly beyond it. Darwin’s latent and, indeed, entrained predisposition to think at this scale –crystalised in his formidable Geological Observations of the Volcanic Islands of 1844— was aimed almost instinctually at the conveyance of originality as scientific intuition. It was a spirit not too different from the one that had assisted Goethe in the inference of his urplantz.

The arc of the Galapagos’ inexorable ferment of Darwin has been likened to a conversion and can be traced over some twenty-five years of watchful thinking. Its earliest symptoms are consigned in his Galapagos notebook; the first dilations of which date from shortly after his return to England.

In 1859, the year in which Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, Alfredo Baquerizo Moreno was born in Guayaquil.

Maps of the Galapagos

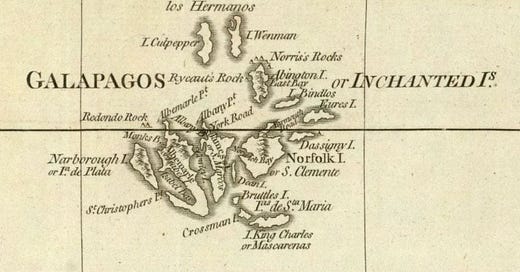

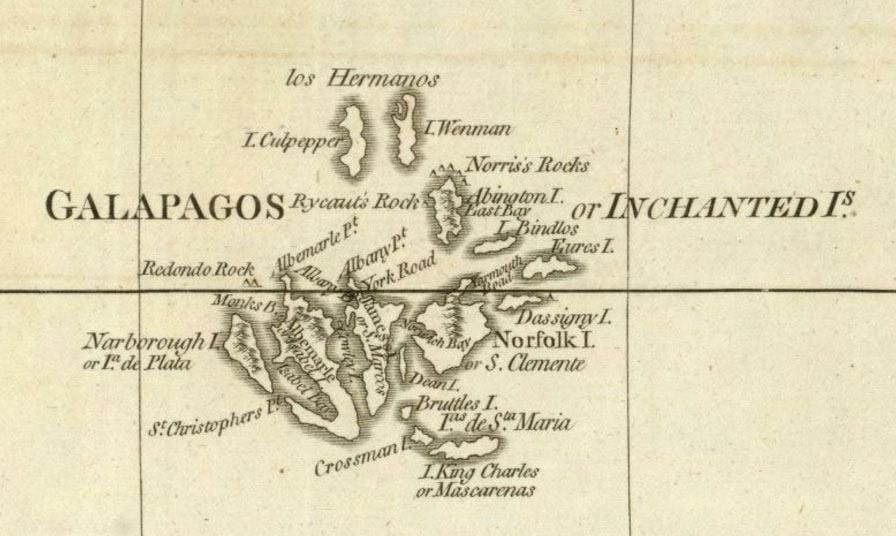

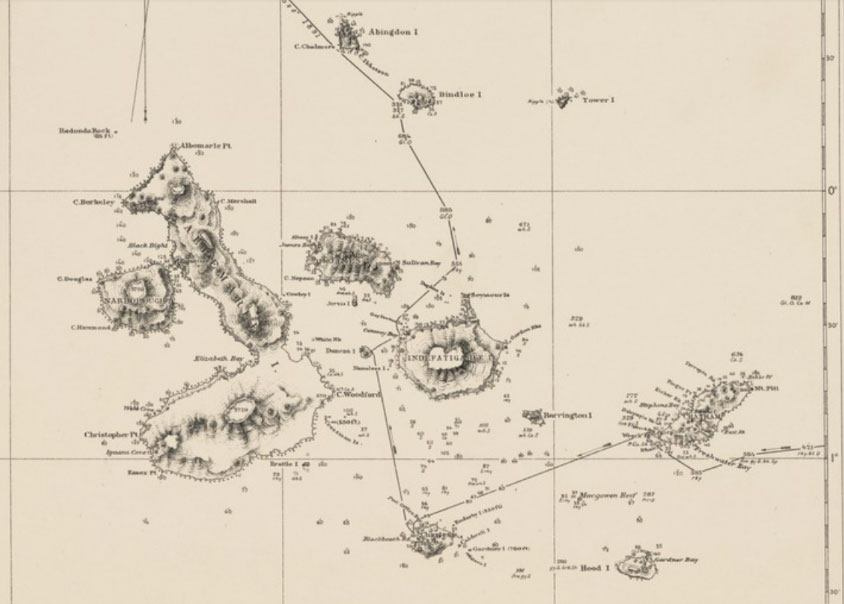

Header: 1776 Extraterritorial: 1694 Antiaeaea: 1710 Saint George the Lonesome: 1897 Depth Perception: 1891

By manner of an epilogue: George died in June of 2012. Six months later, researchers conclusively identified seventeen tortoises that were partially descended from the same ‘subspecies’ as him. By 2015, the discovery of another species, named after George’s caretaker of forty years, Fausto Llerena, was found to have a 90% match to his DNA. Propinquity suggests we may have found the reincarnate William Dampier or some other crewman from the “Bachelor’s Delight”.