Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

The voice now splits like a caduceus. It has become a forked tongue-garden, the ideal climate in which to acquire the language of the birds. There are a few ways to go about it; not too many, not all even secret.

One way to pick up what Dee & Co. would later call Enochian is by tasting dragon’s blood.1

I have licked dragon blood and –in Napoleonic, antiheroic doses– dragon venom. I have been honoured at the Conference of the Birds. I am reforging my [s]word, in all its registers and all its waveforms. I am Kurtz amongst the archons and prepared to die.

You are Roberto Calvi at Blackfriars.

Apropos Birthday

I do not know if the Knossos of doors in Dorothea Tanning’s Birthday —the self-portrait that won her Max Ernst —was in any way inspired by Duchamp’s earlier, liminoid proof that “a door must [not] be either open or closed” at rue Larrey2 though—other than noting the re-semblance —and semblance is its own form of representation—3 this does not disturb me very much among peripherals.

I have lived in a house quite like the one pictured in Birthday by Ms. Tanning, many birthdays ago; it was all doors —all hydraulics— with some leading directly into dead walls; or other, dead, doors; and some to rather strange windows with views to seeming nowhere that may have been thought of as frames for scenes to which I simply was not privy yet –ritual killings, ritual skillsets–.

I have worn ghillie skirts much like the one la Tanning is in, and walked about my labyrinthine confines barefoot and braless, in a nearly identical purple velvet boleador, which is bullfighting attire. At 21, I was already Ariadne.

The only hinge you’ll see in Birthday is a winged cat (provided the cat is a cat, though a wing —any wing— is always at least one hinge, depending on where you cut it). The wings, like the doors —and what is flight but hydraulics— are, again, neither open nor closed, the catlike creature is not flying but crouching close enough to the ground so that we can notice the floorboards themselves are quite unusually aligned or rather, not aligned at all. Everything falls into place then. The ceilings are immeasurably tall, or the doors vertically infinite. The knobs —Ms. Tanning’s nipples included— are the only affordances that one can grasp, or even turn, within a room which is, of course, not a room, either, but a processional: where, if, have you seen a ‘room’ like that, unless it is in a few grand hotel lobbies, with proper sliding dividers, or in a certain house I lived in that was rumoured to have played host to P2 meetings, if one crossed the road across the riverrun?

Did Calvi try to run across the bridge at Blackfriars?

A hanging is also a manner of decapitation; especially a public one, which takes it to the level of performance art, or manifesto. Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and prepare! Nothing beside remains remains.

Hinges, continued

Another extant similarity between the works of Tanning and Duchamp. Hôtel du Pavot corresponds to Tanning’s fascinating period involving soft sculptures of feminine forms —predecessors of Fleshlights, maybe. The insinuation of a den of vices is implicit in the title of the piece, but the need to set the molds up in a room, to give them space, is quite unique within her oeuvre.

The first analogy that comes to mind is Tanning gone Bellmerian, which would be missing the forest for the trees. The ‘hinges’ in Bellmer are rotational: they hint at the plasticity of patella, at the locking and sliding of joints, at the clicking of cogs as genitalia. Bellmer requires lubrication. But there is a hinge Tanning is setting up here that’s much more Duchampian, because it presents as “a transparent surface opening onto a space only to block entry into it”.4 There is no door, in this case, but there is a legible boundary as to where the installation begins.

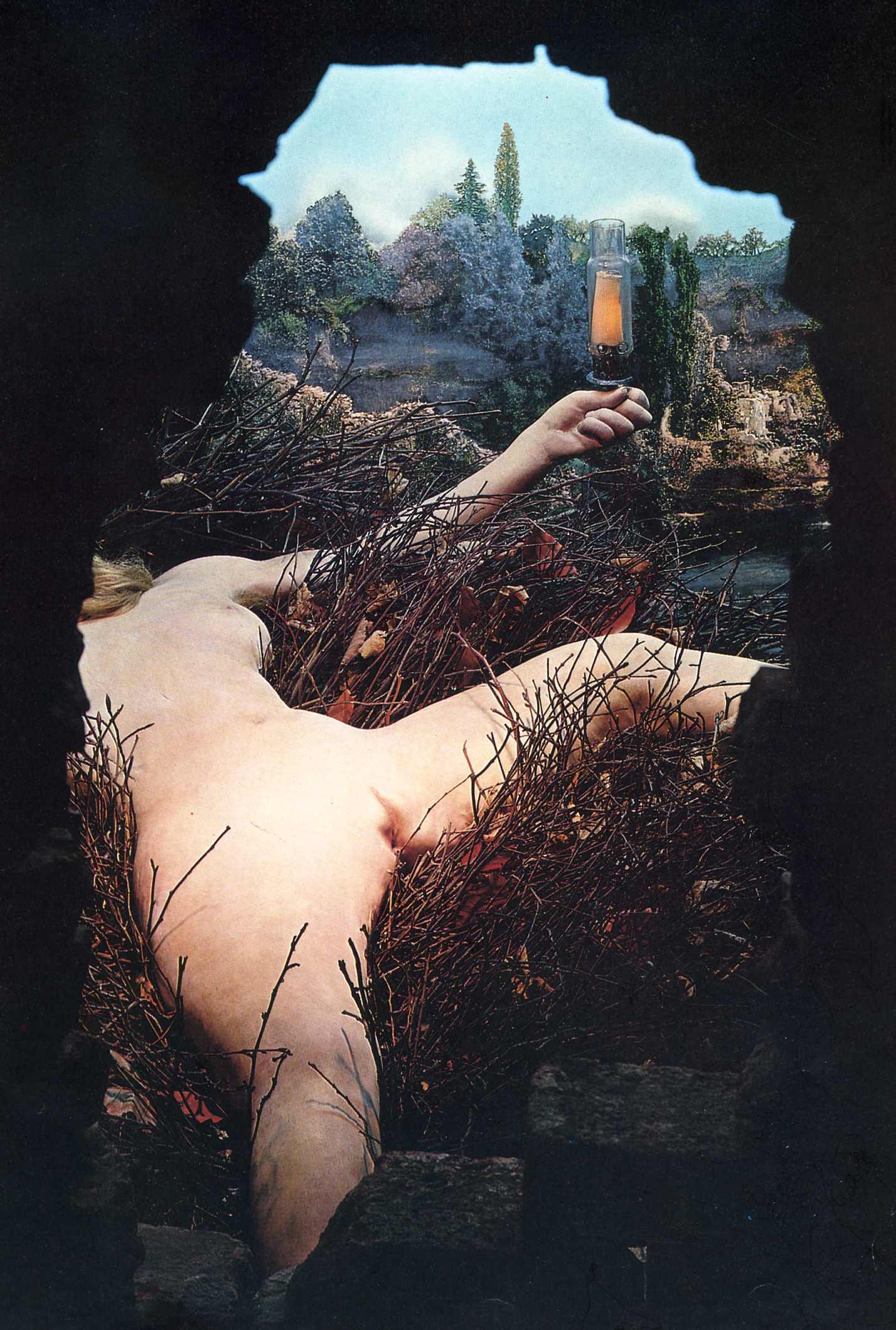

Étant donnés is behind a closed door and a brick wall; a choice Duchamp knew better than to obligate to. This is what is Given to us, per the title. Take it or.

Unlike Courbet’s Origin of the World, which is meant to be ‘looked into’ —pried open and be/held, treated as if Hiffernan’s vulva were a thing of cosmic inquiry— Étant donnés must be peeped at. It cannot be seen at a ‘decent’ remove: that of the amateur –the lover– or the specialist. It forces the perspective of the voyeur and perhaps that of the rubbernecker on the viewer, as the fragment of the body they are looking at resembles —and there is that term again, semblance— the mold of a possibly dead girl, with a curious slit in lieu of, well, the many shapes a normal one could have. The Coubertian inquiry translates into something like a Duchampian injury, or mock-injury.

An immense amount of literature exists around Étant, which remains Duchamp’s most enigmatic and difficult work. This is not an exhaustive reading of it –and I will return to it, as I have and will to the rest of his work over time– and it is meant to focus on one aspect of it only: how it hinges on hinges.

Duchamp has a parabolic type of hinge, impossible to define, and that can only be taught through example —as if, so it can never be mimetically repeated— that is somewhere between the gestural and the conceptual and which he called the infrathin (inframince). It is the indescribable interface; actionable sillage. In Unpacking Duchamp, Judowitz coins from his own Notes that the infrathin is both “a surface (or a screen) and an interval, whose deictical character points in two different directions at the same time.” Étant allows for both, uncomfortably, in ways that other writers have explained at greater length, in greater detail. The foreground is the background. She is dead and alive. Is she even a she, if every mold is intersex. Pataphysics of the gaslight and the waterfall.

But I can leave you with the body of Roberto Calvi at Blackfriars Bridge, swinging either way, in both directions.

Dorothea Tanning. Birthday. 1942. Oil on canvas. 102.2 x 64.8 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Marcel Duchamp. Door, 11 rue Larrey (Porte: 11, Rue Larrey). 1927. Three-dimensional pun: a door that permanently opens and shuts at the same time, made by a carpenter after Duchamp's design. Collection Arman, New York. Courtesy of Arturo Schwarz.

Dorothea Tanning, Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (Poppy Hotel, Room 202). 1970-73. Mixed media. 340 x 310 x 470 cm. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

Marcel Duchamp. Étant donnés: 1. La chute d’eau, 2. Le gaz d’éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas). 1946-66. Mixed-media assemblage: wooden door, bricks, velvet, wood, leather stretched over an armature of metal, twigs, aluminum, iron, glass, Plexiglas, linoleum, cotton, electric lights, gas lamp (Bec Auer type), motor, etc. 242.6 x 177.8 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Which leads to another classic story of decapitation. In the Poetic Edda, Sigurd sits naked preparing the heart of Fafnir the dragon for his foster-father Regin, who is Fafnir’s brother. He burns his finger on the uncooked meat, touches the wound to his lips, and gains immediate access to the language of birds, who tell Sigurd that Regin will not keep his promise of reconciliation and will try to kill him. So Sigurd does what he must: he decapitates Regin with the very sword that Regin had reforged for him. Live by the [s]word, die by the [s]word.

Nor was this the only instance where he worked with this ambiguity surrounding foregrounds and backgrounds around doorways. See the glass Door for Gradiva, which he had designed and then destroyed for Bréton’s gallery of the same name in 1937.

I read semblance as the “to look like” in response to Wittgenstein’s “seeing as”.

Dalia Judowitz. Unpacking Duchamp. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998, p. 213 and ss.