This one’s short but sweet —in the way the scent of decomposing trash is sweet. There are hints of indole to the thing, notes of jasmine and fæces; a tantric gravity to it.

Bloodymindedness is the only admissible form of passive-aggression power should permit itself. It is different from tenacity in that it has an aspect of perversity to it that renders it a bit unsportsmanlike—though it is indispensable to serious competition. That it is frequently adjectivised as “sheer” —its old Churchillian qualifier— is the catch: bloodymindedness it is not about the blood, but its translucency.1

Translucency is, let’s be clear, not transparency. People will not see through you, but they will get a sense of your freedom to insist, which requires a certain openness; a willingness to tip a hand, because you have as many as an Indian god. Bloodymindedness has sprezzatura to it, something that cannot be said for any of its seeming synonyms.

Now that reading Russell on philosophy appears to be in vogue among the kids, may I suggest another —far more worthy— prison writer who, to my mind, stood for bloodymindedness in the most aesthetic and fantastic way possible. I am obviously referring to the divine Marquis, whose life was sheer —in its absolute, perpendicular and translucent senses— to a degree which earned him the most coveted epithet on Earth —at least for some of us— courtesy of Apollinaire, the arbiter elegantiarum of the Einsteinian-era avant-garde: Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade, was “the freest spirit that had ever lived"—despite having spent 32 years in a panoply of prisons, including the Bastille as it was stormed.2

If one are free, one can be locked away, and History will still pay you a conjugal visit.

One aside, because Onfray, the author of Les libertins barocs, reminds us that Sade is no hero. And indeed he is not. Sade is a model: often wrong and vastly useful.

Bloodymindedness is not libertinism; it is a discipline in will that can be libertine, or not at all. Like Casanova before him, Sade does not persist because he was scandalous, let alone cruel (unlike, for instance, Cesare Borgia). Sade captures the imagination because he was free, in ways a force like William Blake might be free.

Now, freedom always means encroaching on the freedom of others. One must have the decency to do so with a ruthless elegance. That’s where the bloodymindedness comes in.

That’s what it’s for. That’s what it is.

Encroach freely.

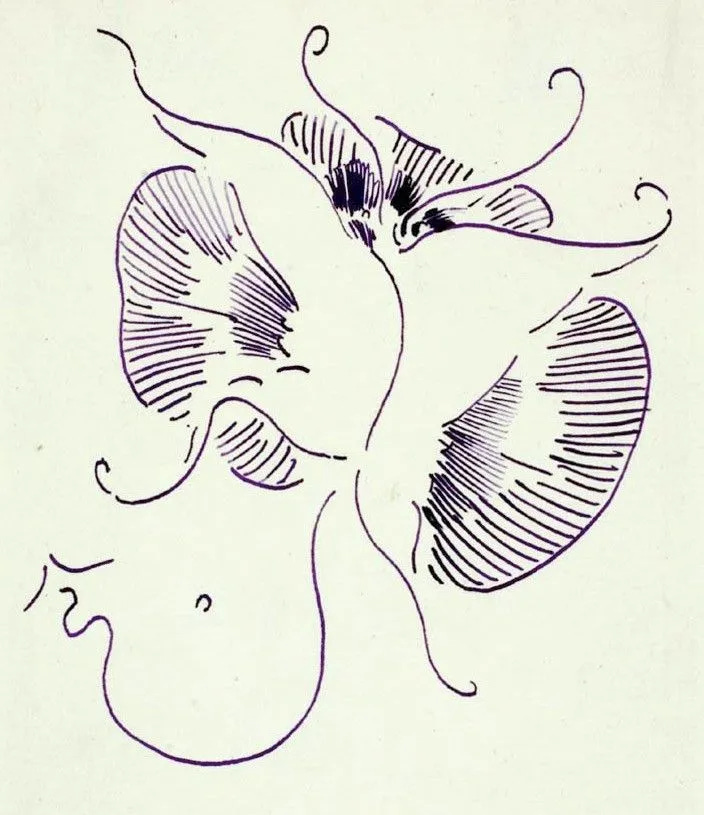

PS: You know who else was bloodyminded? Whistler, the impossible American, here:

Hemoglobin affects the colour of blood like porphyria impacts the colours of urine. My Faustian novel includes a courtship by a porphyriac Russian count that involves sending his beloved astounding chromatic variations of his urine; a Scriabinesque colour-wheel.

After which he was packed to an asylum for inciting a crowd during the event.

The signatures are Sade and Whistler’s famous butterfly-with-a-stinger.